2014 was a helluva year for Vladimir Putin. He’s the first European leader to expand his state since West Germany and East Germany united in 1990. He’s the first since Stalin to grow it through military force and get away with it. He’s enjoyed sky-high approval ratings, outmaneuvered Obama on Syria, Ukraine, and, arguably, Iran, and turned a basket-case of a nation-state back into a great power.

Too bad he’s super likely to lose it all anyway.

The cliff notes! Oh, cliff that note.

- From 1999 until today, Russia under Putin has been super successful at stemming the bleeding left over from the collapse of the USSR.

- That certainly is a success, but it’s not the same as eclipsing the United States.

- The United States has critical geopolitical factors that keep it #1.

- On a long enough timeline, no matter who the American president is, the Russians will be overwhelmed by those factors.

So, now for the dirty details. And lo, the year is 1991

The Soviet flag was lowered at the Kremlin for the last time on December 25, 1991. From 1992 unit 1999, Russia experienced a series of geopolitical knocks that would have destroyed a weaker state. Secession, especially in the Caucasus, was rife; Chechnya fought off the demoralized Russian army in 1996. The ruble collapsed, President Yeltsin seemed drunk most of the time, and the victorious West spent much of the decade thinking about what to do with world domination.

It was the lowest moment for Russian power since Hitler was on the gates of Moscow.

Russia’s greatest strength has always been its sheer size: both in land and population. It can afford to take losses others couldn’t. Consider these huge losses: it went from a high of 290 million people in the late Soviet Union to a mere 148 million under the Russian Federation (equivalent to losing the population of the United Kingdom almost twice, and nearly 50% of its entire population). On top of that, it went from some 8.65 million square miles of land to 6.5 million square miles of territory; equivalent to losing about 47 states the size of Germany.

How many other nation-states have lost half their people and a third of their territory in less than two years and lived to tell the tale?

It was inevitable that Russian power in the aftermath of such a defeat would be chaotically used and badly managed. That lull led many to believe that Russia would either remain a basket-case forever or, best case scenario, a compliant member of the international community. The latter was given a lot of credence when Russia cooperated to remove Soviet nukes from former republics.

Ha! Like that was going to happen.

Russia’s geography favors strong, centralized states because of its huge, hard-to-defend territory. Too much authority can’t be given to locals, or they risk forming splinter states and eventually seceding. (That’s pretty much why the Soviet Union collapsed; the USSR had sought to improve upon the overly-centralized czarist government by giving more power to local soviets, or governing councils, in different republics. That blew up in their faces when those soviets started to vote to split the republics off from the Union).

So Russia had two choices: either to continue to fragment, splinter, and end up a much-reduced, Balkanized remnant of its former self, or to use its still-formidable powers to run Russia the way it had always been run.

Guess which one it did.

Putin’s high marks come from his ability to see modern Russia for what it is: a neo-empire, requiring neo-imperial methods for control and defense.

First was restoring Russia’s fighting ability. The collapse of the USSR may have shrunk the borders, but vast stocks of military goods were still more than available for Moscow to deploy, including its formidable and potentially world-ending nuclear arsenal. They just needed someone to come along and kick asses like all of Russia’s great rulers had done.

Second was restoring stability in politics: in Russia’s case, that means predictable transfers of power between small, controlled groups of elites. Frankly, not just any person can be allowed to run Russia; there’s just too many regional and special interests (imagine a Chechen winning the presidency!)

That meant rolling back some, but not all, of Gorbachev’s glasnost. A fine example of this is Gorbachev’s famous Pizza Hut commercial. (A highlight of my childhood, being the only 1st grader in 1991 to know there there was something called the Soviet Union collapsing). That commercial admits Russia’s faults, but names nobody specific beyond a discredited leader, and then agrees to just eat pizza.

Glasnost had gone too far; it had named names, and corruption had a face in the Communist Party. Russia’s elites realized that they couldn’t pretend everything was well and good in their new country, but they could pretend it was impossible to find out who was responsible.

The 1996 presidential election began this process in earnest. Yeltsin, weak and feckless though he was, represented the new Russian elite, while his opponent, Communist Gennady Zyuganov, represented the holdouts from the Soviet regime. Both forces represented attempts by Russia to reorganize its still formidable power and undo the unraveling, but the Communists were a failed past. Yeltsin’s campaign team manipulated the media to stunning success; Yeltsin even had himself a heart attack and won the presidency anyway.

Which shut out the Communists for good and replaced them with weak, predictable opposition parties.

The door had been opened; Russia’s new elites couldn’t just run the country as a dictatorship. But they could set up many a straw man. When the Communists lost the ’96 election, it was the end of them as a true alternative to the new rulers in the Kremlin. From that point on, the Kremlin, dominated by former KGB men, began to use their old spy craft to set up puppet parties, NGOs, and other forms of “opposition” that could be neutered whenever they got too serious.

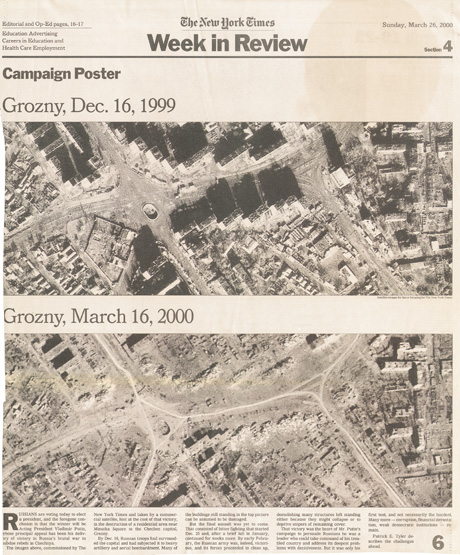

The central geopolitical rule of a strong, dominating central government was reinforced. Concurrently, Russia’s army started fighting better. By 1999, Yeltsin was preparing to be pushed aside, and from the ranks emerged Vladimir Putin. One of his first major acts was to invade Chechnya and put an end to secessionism there.

Putin utilized all of the USSR’s former superpower tools to claw Russia back out of its hole.

Russia didn’t lack for tanks or guns; it lacked officers and soldiers capable of using them well. Putin sorted that through purges, reorganization, and political stability. Doubters were pushed aside. But Putin didn’t have the ideology of the USSR to underpin his actions; he had cash.

This was key to the new Russia. The only thing that could bond the new elite of Moscow was money. Communism was a farce; religion had long been undermined by the Soviets; even nationalism could feel hollow. So Putin made a new social contract: the loyalest get the spoils.

In a way, all our political systems are held together by the same glue. Vote for me, and I’ll give you prosperity. But Putin targeted carefully; the generals, spies, and criminals who had been fast enough to gobble up the Russian economy in the 1990s were key to his rule.

Not everyone thought highly of Putin, of course. But he had a powerful card to play. In post-Soviet Russia, legal confusion was inevitable; what laws were Soviet and what laws were Russian, and which were in effect? At one point or another, virtually everyone could be accused of a crime. Putin made it an art form of simply noticing the crimes of his enemies. To cover the gaps, Putin’s people rewrote laws to take down people clever enough to cover most of their tracks.

It wasn’t the same as the Soviet terror; rather, it was Putin confusion. Nobody knew if they were doing the right thing or not; what they did know is that the majority of people being arrested were those who too openly opposed the president or his supporters.

It was a careful balance between appearing to be free and actually being under an authoritarian state.

Russia as it stands today must be ruled by an authoritarian government. If it becomes too democratic, it will break up; there are just too many agitated ethnic minorities within its borders. That will drop Russia even further down the power ladder.

Putin took the Soviet model of propaganda and brought it into the 21st century. Rather than claim to have the truth, he sowed doubt and counter-claims. Rather than use ideology completely the opposite of the West, he took the West’s methods of journalism, transparency, and information sharing and distorted them, inverted them, and twisted them to make most of them seem unreliable. It was effective and still works. Even when abundant evidence amounts that Russian-backed rebels shot down Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 last summer, conspiracy theories abound about it being anyone other than the most obvious culprit. That is proof of how good Putin’s government has gotten at creating confusion.

With internal threats sorted by 2008-09, Putin could then focus on external ones.

Following the end of Soviet power in Eastern Europe, NATO and the EU surged forward. Both of them had political models that would have been deeply painful for modern Russia to adopt: both demanded transparency and democracy on levels that were a mortal threat to Russia’s territorial integrity and great power status.

Putin knows that NATO won’t invade Russia. But NATO states on his borders are potential bases for separatists and opposition to his rule. What if Georgia had joined NATO? Certainly, Chechen rebels could use Georgia with impunity to run a forever war within Russia. What if Ukraine joined the EU? Certainly, Ukrainian media outlets could undercut and undermine Russia. If successful, Ukraine could even inspire Russians to want to join the EU itself, which could mean the end of Russia as an independent power.

Such “coulds” and “mights” are enough to warrant Russian action.

Now Putin is using all his powers to push American and Western power back as far as he can.

Mutually Assured Destruction is still very much in effect: both nuclear powers are well-armed enough to end civilization. That culture of MAD forces the struggle to be by proxy.

But Russia is not the USSR; to compete for too long will result in another defeat.

Russia’s losses in 1991 knocked it out of superpower status. It’s now confronting the very enemy who defeated it, but this time is trying to be more subtle. Much like how Putin took the Soviet propaganda machine and modernized it, Putin is also taking Soviet diplomacy to the 21st century. That means sowing confusion, avoiding black and white struggles, and being careful to pick fights that he can be sure he can win.

He’s won the early, easy battles. He got away with crushing Chechnya and Georgia; both have been eliminated as security threats. Now he’s taken the biggest risk of his political career by embarking on war in Ukraine. Even there, however, he’s trying to show moderation; rather than a full-on invasion, he’s used proxies whose identity can’t be clearly ascertained. There’s just enough doubt to sow dissent amongst the Europeans; maybe these Donbass rebels are authentic, some ask?

He’s also been lucky. The United States under Obama is more divided than American government has been since the Gilded Age in the 1800s. The U.S. can’t formulate policy and deploy its power as well as it could in the Cold War. That has meant an opportunity for Russian power to surge into the gaps.

This division in American government is one reason foreign policy elites are trying to decide whether the U.S. provoked Russia by expanding NATO. NATO expansion was feckless; it just sort of happened with no big strategic goal in mind, and suddenly Western elites are surprised to find the Russians don’t like it.

Inevitably, the United States will reorganize itself and project its power more fully; that will be fatal for Putin’s Russia.

The U.S.’s greatest strength is its regular election system. In 2016, Obama will go; the next president will inherit a mandate to do something about Russia. If that president fails, and Russia grows stronger, they may lose in 2020; that next president will then be given a stronger mandate to do even more about Russia.

Either way, no president will be elected from now on with a platform of “Don’t worry about Russia.” Each election will ratchet up the pressure the Americans can bring to bear on Moscow. That pressure is considerable.

Russia has no Iron Curtain to fall behind, no idealistic ideology to use, nothing besides greed, confusion, and paltry nationalism.

The Soviet Union could draw upon its satellites to shore up its own economy. It could mobilize its citizens with ideology to accomplish things that the czars could only dream of. But Putin has none of that. He can bribe more elites, keep Russians confused and therefore disorganized, and pull upon some threads of Russian nationalism. But none of those are strong enough to save Russia from American power.

Witness the already-nasty sanctions regime; this is just round 1, and the ruble almost collapsed last December. What if there was a total ban on Russian exports? What if the Americans traded some islands in the Pacific for an alliance with China? The American military machine is, in many ways, in a better position today than it was in 1991. It now has bases inside the former USSR itself in the Baltic states and a NATO that includes big chunks of the Warsaw Pact.

The U.S. is about $10 trillion richer by GDP than it was in 1991 (from roughly $6 trillion to just under $17 trillion today). Russia, while better off than under the Soviet Union, still only pulls in $2 trillion a year; worse, far too much of that is dependent on oil, which the Saudis and Emiratis have gutted in price.

The hotter the competition becomes, the greater a percentage of GDP will be used by both sides to get what they want. The U.S. did not lose a decade of prosperity and military advancement in the 1990s; if anything, the U.S. was getting better at both economics and war. Russia has done a lot since 1999, but nobody should mistake that for anything other than fixing a very broken system.

Some will point to the Financial Crisis, the Iraq and Afghan Wars, and the many little failures of American policy as proof that Russia is winning, but that’s missing the point.

American grand strategy has not been affected by any of these three events. U.S. grand strategy is more secure than ever: the U.S. Navy controls all the world’s oceans, the U.S. military can deploy force in any non-nuclear nation on Earth, the U.S. alliance system is at an all-time high (44 formally allied nations, 28 NATO and 14 Major Non-NATO allies), and the U.S. remains poised to become an energy superpower.

Russia, meanwhile, is better than it’s been at any point since 1991. But it’s nowhere near the superpower status of the Soviet Union. Russia has won tactical victories, not strategic ones. That’s part of the reason Putin has accomplished so much; he’s actually accomplished very little geopolitically. Russia has gone from defunct back to a major regional power; that’s nice to put on the resume. But it’s nothing compared to what the U.S. has done in the same time period.

Had Putin actually altered the balance of power, the U.S. would have reacted in a much larger way. The war in Ukraine threatens to do just that; hence the sanctions and the deployment of force to Eastern Europe. But it’s still a small enough affair that the U.S. can dither; dither it will, too, until Russia enjoys a success big enough to scare Americans into action. Not even the fall of France could stir America to action in World War II. The beginnings of American wars are like Americans themselves: mostly dramatic, susceptible to hype, and rarely well-organized.