Rodrigo Duterte, who famously told President Obama to go to hell, is bringing Russian trucks and guns to his country. But the Americans aren’t worried. According to Reuters:

U.S. Ambassador Sung Kim played down any U.S. concerns about Duterte’s outreach to China and Russia and noted that the United States, a former colonial power, was the country’s only treaty ally, with far deeper ties in the Philippines.

“I‘m not really threatened by this notion that China or Russia are providing some military equipment to the Philippines,” Kim told a small group of reporters traveling with Mattis.

“We have been providing very important equipment to the Philippines for many, many years. The fact that the Chinese and the Russians have provided some rifles, I‘m not sure is really such a cause for concern for the United States.”

All true, and, for the medium term at least, substantial. Yet the once crystal-clear geopolitics of East Asia are growing dim and confused with each day, thanks in no small part to the changing dynamics of the Philippines itself. For long term American strategic thinkers, the Philippines should be a cause for concern, for within it are the deeply buried seeds of the multipolar world that both China and Russia seek to build.

The American-Filipino alliance has been tested by upstart President Rodrigo Duterte, often called Asia’s Donald Trump, who has cursed the U.S. in one month and then played the supplicant the next. When criticized for his brutal war on drugs by President Obama, Duterte threatened to jump ship to Russia or China. Then, in May, he revealed that China threatened war if the Philippines tried to drill for oil in the disputed South China Seas. So much for a warm welcome.

It’s all very confusing. On the one hand, rock-solid geopolitical anchors compel Manila to remain in the American camp. The Americans are the primary arms supplier and trainer of the Filipino military, and replacing them effectively would take years and would be unpopular with the country’s generals. The Chinese still want the South China Seas all to themselves, something that threatens Filipino trade, energy independence, and fishing. The American defense treaty would have to be overturned before a true pivot could happen, which would require the Philippine legislature to both ditch the U.S. and agree on a new sponsor. Finally, neither the Russians nor the Chinese want to fight the Sunni supremacists of Mindanao; only the Americans are willing to help that job.

All those obstacles are good reason to believe the American alliance with the Philippines will survive Duterte’s five-year term intact (Filipino presidents are limited to a single term).

Yet this to imply the world is still divided into the either or of the Cold War. As the years wear on, it’s no longer reasonable to see Manila as being in either the American or the Chinese camp, but in fact trying to get the best of both.

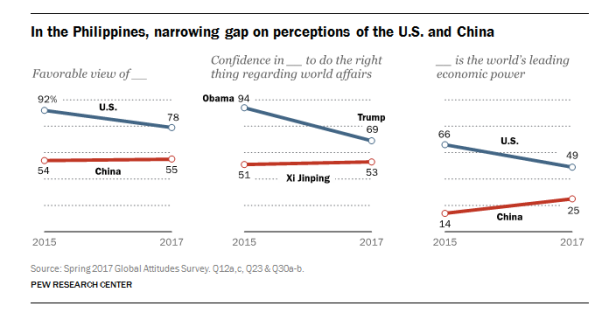

Shifting perceptions as Filipinos warm to China

Strikingly, Filipinos have a higher opinion of China and a lower opinion of America than anytime in recent memory. According to a September 2017 Pew survey, on just about every indicator the survey measured, the gap between China and the U.S. has narrowed dramatically from 2015 to 2017.

A good deal of that could be the Trump effect: Trump is notoriously unpopular globally. Yet the third perception indicator – that of economic prowess – is key. As America and China increasingly appear to be economically equitable, opportunity exists for Beijing to make inroads into the American alliance system.

China’s much-touted One Belt One Road initiative is already the soft power play to do just that. When Trump killed the Trans Pacific Partnership, he also set American geopolitical efforts back and gave an opening for China. Now President Xi is barrelling ahead with China’s alternative, which will include the Philippines.

Since East Asia’s geopolitics rarely force states to choose clean sides, Manila will have every incentive to hook itself into China’s vast market as much as possible while keeping its defense ties with the United States. Yet if the United States appears unreliable, it will tempt future Filipino leaders to find an alternative of both arms and security. The popular perception to choose China is beginning to emerge.

One other very real possibility is that this is merely a fad – and once Duterte and Trump’s petulance leave the world stage, the Filipino-American alliance will return to normal. The Filipino military might end up saddled with token equipment from Russia and China they have little interest in learning how to use, reduced to museum pieces. That is what happened with Egypt, who flirted back and forth between the Americans and Soviets until the U.S. finally outbid Moscow. Now most of Egypt’s Soviet equipment sits as historical relics of Nasserite bait-and-switch. Perhaps Duterte’s shipment of Russian trucks and rifles will do the same.