I’m in Washington D.C. this week, and good God will they not shut up about him. Treason! cry the hardcore conservatives. Hypocrites! cry their enemies. All in all, it’s very annoying. But beyond the headlines of dummy-wandering-off-base-and-getting-captured-for-five-years-and-does-that-make-him-a-bad-person lies the real tale of the U.S. trying to pull as much it can from the unsolvable war in Afghanistan.

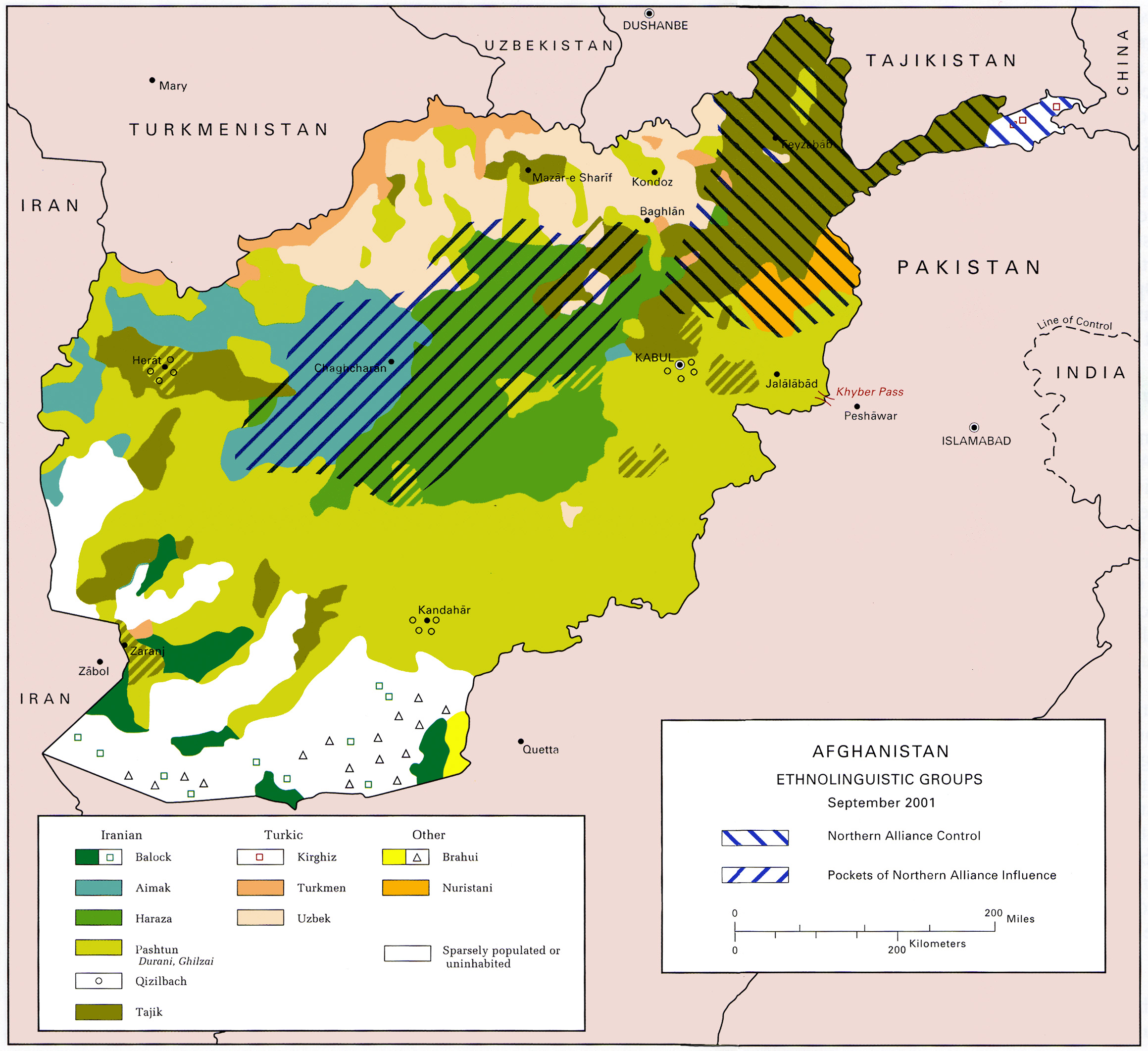

Issue #1 – Afghanistan is a geographically fractured country with a variety of potential nations within it

Historically, Afghanistan has been the edge of an empire rather than the center of it. That’s because the high mountains, harsh deserts, and difficulties in moving stuff from A to B have led a lot of would-be kings set themselves up outside of some emperor’s or world conqueror’s reach. An army might move into the country, defeat the myriad tribes there, and declare a province, territory, or occupation zone, but the difficulty then becomes that Afghans have the ability to easily organize guerrilla wars – which have now become something of a national pastime.

Issue #2 – The process of building Afghanistan into a modern nation-state can take no less than generations

Human capital inside the country is rotten. That means the vast majority of people have no idea how to function in anything but a tribal setting, and so they can’t wrap their heads around the idea that a national police, army, or government is a good thing that they should wholly support. Rather, they will distrust these institutions of strangers because that’s what a tribesman does.

To break this mentality requires two things: a government that can accomplish things well and an economy that can pay for said government. Afghanistan has huge hurdles to getting either.

They haven’t even agreed on what a regulation beard should look like.

Issue #3 – American policymakers in 2001 assumed a weak state like Afghanistan could be easily transformed

After World War II, America helped rebuild war-torn Europe through billions in loans that prevented Soviet-inspired communists from getting the breathing space they needed to overthrow what remained of Europe’s democracies. It worked – stunningly. But it worked for one very key reason: Europe’s human capital was up to the task. Germans, French, Italians, and British did not need to be taught how to run a factory effectively or build a bridge; they just needed the goods to do so.

In 2001-02, American leaders thought they could copy the same model and apply it to Afghanistan. But give a tribesman a billion dollars and he will remain equally ignorant of how to build a hydroelectric dam. Training him properly will take up to a decade – that is, if he finishes such schooling at all and you haven’t made a huge error letting him into your dam building school.

What Americans assumed – and were wrong about – is that changing Afghanistan’s cultures would be as simple as writing a check. Culture is immune to bribery; it changes only when the environment dictates it should, and only when such dictation is repeated. The barrel of a gun can be a part of that, but never the heart of it. Economics and human geography must change.

Fast forward to Obama’s failed surge, which just proved the point

After the 2010-11 surge did not break the back of the Taliban, it became obvious that the only solution left for Afghanistan was a more-or-less permanent occupation as the necessary cultural changes occurred at a pace set by the locals. Hence the treaty that leaves U.S. soldiers in the country, but not actively fighting. Such a force can keep a government in power in Kabul, but little else. That’s about the best one can do in such a fractured place that still lacks basic roads.

But why the sudden rush to tie up the Bergdahl loose end?

Much of this has to do with the internal geopolitics of the United States. As a large, diverse country, the U.S. is run as a federal system with several centers of power intentionally divided against themselves. The U.S. has been centralizing a great deal since World War II, but D.C. hardly has the power of say London or Paris in deciding policy for the whole country.

In an Information Age democracy, government scandals move at the speed of light. These scandals are, in the current political culture, virtually the only way for factions to achieve more power – general elections routinely return the same candidates again and again and have diminished in importance. And so a president who wishes to tie his legacy to ending wars can leave no threads by which opponents can grab hold. Freeing Bergdahl made political sense in a system like the United States’.

At the same time, attacking the swap makes sense for Obama’s opponents. From a geopolitical standpoint, the five Taliban now in Qatar are not terribly dangerous – as the Taliban itself is not a very formidable opponent, merely an annoying guerrilla force that will die out only once the culture it thrives in disappears. But the scandal they are now part of is incredibly useful for the Republican Party, who can use it to try to achieve what power is now achievable in America’s dysfunctional political culture.

Irrelevant gents, but boy it doesn’t help that they genuinely look like they’re plotting in their mug shots.

The war is ending; let the blame game begin

America’s political culture is not ready to accept that nobody could have won Afghanistan; that, in fact, the goals were over the top, and a better strategy would have hinged on local, but deeply undemocratic, strongmen who could have overseen the cultural change and economic development that Afghanistan needs to enter the 21st century. And so inconsequential things like Bergdahl will get headlines; they will be the talk of the town for a news cycle or two. And then we’ll move on to the next scandal.