Sex! Drugs! ATM bombs! A long-running violent uprising against the government! What’s not to love?

When I first visited Bahrain in February 2011, just a few weeks before the mass uprising that would happen later that month, immigration stamped my passport with a big, “BUSINESS FRIENDLY BAHRAIN” before waving me through the mostly empty airport.

When I returned two years later in February 2013, there was no mention or either business or friendliness as they scanned my passport for evidence I might have been a human rights worker or a journalist come to document the government’s thuggery.

While before 2011, Bahrain was known for its liberal mores and as a decaying 80s party spot (or, if from outside the region, not known at all), it’s now synonymous with sectarianism, fighting, Molotov cocktails, and weekends protests. Bahrain might be a tiny place, but its problems are far bigger than its geography implies.

Welcome to Bahrain: the party island where the party might actually kill you

Think “Persian Gulf” and you think austere Saudi beards or out-of-control, ultra modern Dubai music videos. Bahrain is somewhere in between and has the distinction of being one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the Gulf. As such, it’s got less of the cultural immaturity of other new Gulf states still finding their footing in the modern age and more of the hang-ups of a country that’s been around to have serious internal grudges. Underneath Bahrain’s land are two resources that guaranteed it a place at the heart of the Gulf: an oasis and easy-to-grab oil.

Until the 1930s, the Bahraini oasis and its relative isolation from attack made it one of the biggest ports in the region. One group, the Qarmatians, in their brief but awesome run as rulers of the island, set up a republic, sacked Mecca, and stole Islam’s Black Stone from the Kaaba before they ran out of energy and fell apart. After that spate of piracy, Bahrain spent most of its history under domination from imperial powers, ranging from Iran to Portugal to finally Britain in the 19th century who were keen to ensure that no Persian Gulf Tortuga established itself there.

To get an idea of how key Bahrain was in the pre-oil era (and to understand just how unimportant the Gulf in general was before oil), it was the residence of Britain’s colonial Political Agent, who, as a sort of latter day Roman proconsul, managed the Gulf on Britain’s behalf. In other words, while Bahrain was the most important place for the empire in the Gulf, it was so unimportant in the grand scheme of things that Britain assigned just one dude and a small staff to it.

It was under Britain that oil was first found in the 1930s, sparking the oil rush in the Persian Gulf in general. That oil rush, along with its long history as a settled place, helped Bahrain develop culturally into the closest the Persian Gulf has to a modern nation-state. Trade unions set up; political parties were established; the British worried about communists taking over the government. By the time the British withdrew in 1971, Bahrain’s power struggles were already in play. To ensure things remained complicated, as the British left, the Americans sailed in.

Throw in some sectarianism and you get the drift

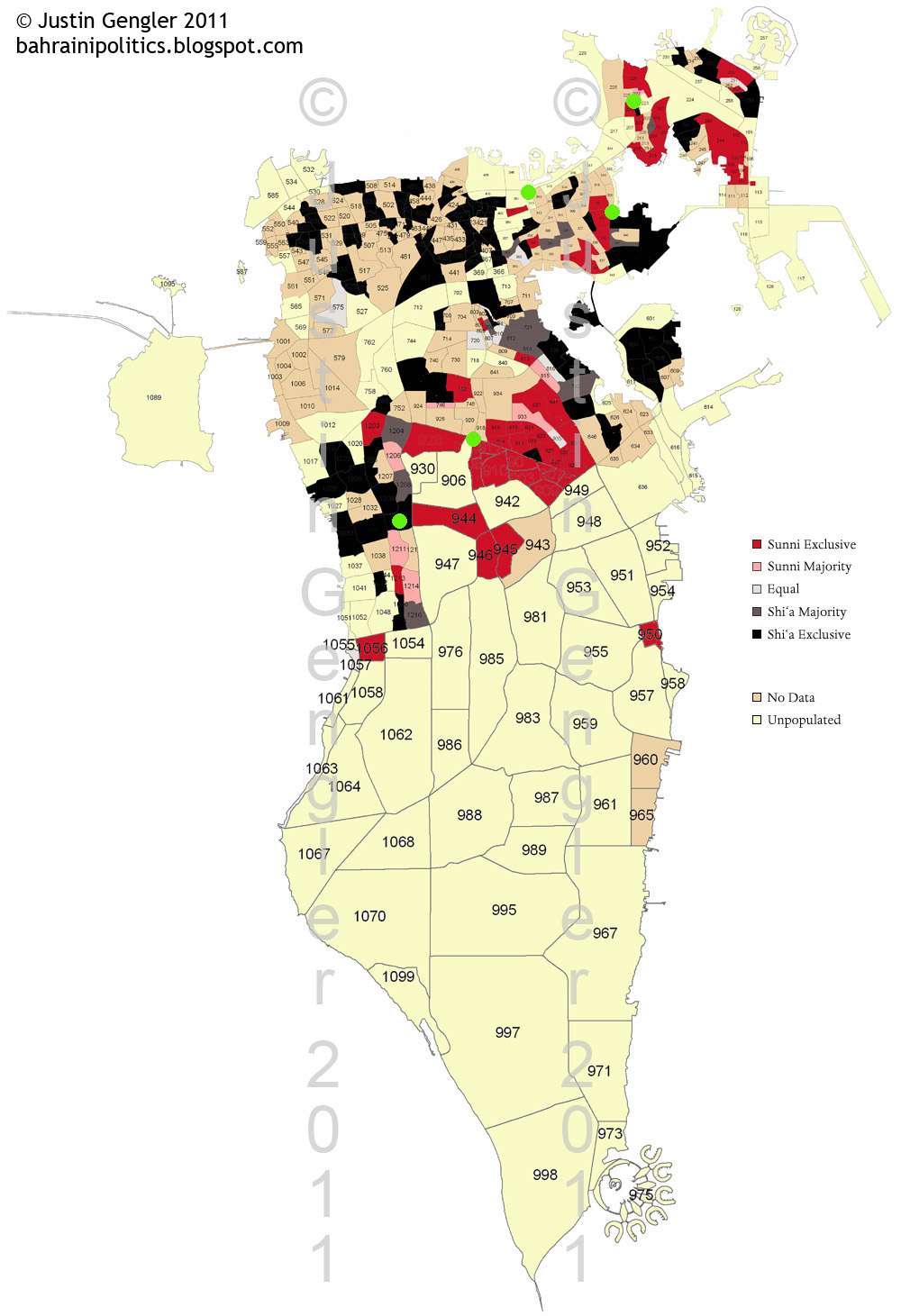

As a tiny place, Bahrain’s struggles were always local. In the 1970s, Bahrain’s central government struggled to tame the many forces that sought different visions for the country. In the beginning, while the Shi’a/Sunni divide existed as a result of Bahrain being a borderland between Shi’a Iran and Sunni Arabia, it was further subdivided between those who sought a republic, a communist utopia, a democracy, a traditional sheikhdom, and all kinds of other political models. While in the 1970s the wider Gulf wasn’t much worried about politics as they started to build their societies, in Bahrain power was in flux.

Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution threw another wildcard into the mix, introducing Shi’a political Islam as yet another future for Bahrain. In 1981, some Shi’a attempted a coup to seize the country. From then onwards, the leftists, Arab nationalists, republicans and democrats started to choose sides between the two sects. The USSR’s death in 1991 pretty much ended the Bahrani communist party (along with every other minor communist party worldwide) and the left merged to become part of proto-modernist secular movement seeking some kind of democracy. With Shi’a political parties pushing for one set of things, modernists and secularists pushing for another, and Sunni traditionalists propping up the government, the result was a series of ploys, plots, riots, and lies as each side jostled for the best power position.

The 1980s weren’t all bad, though. Lebanon’s civil war sent many banks scurrying to Manama to set up shop as Beirut cannibalized itself. Much of the capital was built during this time (and shows today) and the country set itself up as a party spot for bored businessmen stuck in Saudi Arabia or other dire Gulf states. Before Dubai took the model and went nuts, it was Bahrain that you wanted to party in.

But for all the fun of the 1980s, the 1990s were a decade of stagnation, occasional bombings, and intifada. Opposition groups rightly pointed out that loyalists were getting the plum pickings of oil revenues and jobs and formed a coalition of Islamists, secularists, and democrats who sought to turn Bahrain into a more accountable constitutional monarchy. The government decided that was a terrible idea and cracked down. From 1994-2001, Bahrain wobbled. Hardly anyone outside the region noticed as the roar of the stock market and the killing fields of Bosnia crowded out what news came from Manama.

To put an end to the uprising, the Emir, Hamad al Khalifa, offered a series of compromises that changed the country from an emirate ruled by an emir to a kingdom run by a himself. This was accompanied by a few concessions that gave power to a handful of opposition figures. It was bullshit and everyone knew it, but exhausted after seven years of protesting and willing, in typical Gulf style, to give anything a go once, the switch bought several years of relative quiet. Until Mubarak fled in 2011 and the Bahraini opposition thought to have another run at revolution.

Being caught between Saudi Arabia’s paranoia, Iran’s ambitions, and a part of the world that’s having trouble growing up is not a nice place to be

For Saudi Arabia, Bahrain is a bell weather for its own Eastern Province where quite a few Shi’a live – and where quite a few Shi’a are not happy with King Abdullah. Once upon a time Bahrain served as a base that marauded Arabia. That might have been a thousand years ago, but Bahrain’s geographical location could let it do so yet again if it were to fall out of Saudi Arabia’s orbit.

Meanwhile, Iran officially would love everyone to embrace its Islamic Revolution. A natural expansion point is Bahrain with its Shi’a majority. Iran has said again and again that it’s not involved in the simmering rising. But it’s reasonable to assume, like much governments say, that’s a lie. Iran has every incentive in the world to destabilize Bahrain.

Meanwhile, other Gulf states like Qatar and the United Arab Emirates feel deeply insecure in a region where they historically have been dominated by either powers based out of western Arabia, Iraq or Iran. With vast natural resource reserves, these states have double downed on alliances with the United States in hopes that that will provide border security while ruthlessly crushing internal dissent. No one state may wobble; they are all built on the same foundations of sand.

And the Bahraini opposition has hardly given up

Bahrain is the only place in the region where the Arab Spring is alive and fighting. As a small country with a relatively low population, it teeters on a knife’s edge, and only outside support has kept the current king in power. Demographics matter and not in regards to the majority/minority game. In a small country with a small population, the actions of a few hardcore activists carry more weight than in bigger places. When a few hundred protesters seal off a neighborhood in Bahrain, that’s 10% of the country. When a few thousand decide armed struggle is the way forward, that’s a country-wide civil war.

With Saudi forces in place and UAE police back-up, Bahrain’s outnumbered government can hold the line. Bahrain is more or less occupied by these forces and the United States naval base. While U.S. soldiers have nothing to do with the Shi’a uprising, they do force Iran to keep its support to a level that the king and his allies can handle. The last thing Iran needs is to provoke the U.S. in the delicate on-going nuclear negotiations.

Bahrain’s rebellion smolders. I was there two weeks back; I saw a neighborhood sealed off by police and army units while an attack helicopter circled, proof enough that things have not gone as quiet as the world media’s silence implies.

But a splintered opposition makes it all the harder to achieve real change

Bahrain, like all the Gulf states, went immediately for the sectarian card as soon as the Arab Spring began. Any opposition to Gulf regimes was a Shi’a/Iranian plot to destroy Islam and the country. This wedge has worked for now. Sunni secularists don’t protest with Shi’a Islamists like they once did. Fear and hatred has grown between the communities, stoked by a relentless state media that has witch-hunted protesters on Facebook. Shi’a, meanwhile, have split between the old guard that favors a constitutional monarchy and radical, younger groups that want full democracy, Shi’a theocracy, or something in between. For the young Shi’a now having grown up with street battles and burning tires, the al Khalifa royal family has no future in their country. “Death to Hamad” is their battle cry.

Alas, Bahrain will not likely decide what happens to it

Left alone, on a long enough timeline, the al Khalifa family would eventually be pushed into the sea. But they have big friends. Powerful geopolitical interests of much bigger states wish to see the status quo continue.

To lose Bahrain could provoke a full-fledged rebellion in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province and threaten world oil markets. No Gulf state or Western power wants that. To that end, Saudi Arabia’s military provides the edge needed to keep the demographic destiny of Bahrain from taking place. The West will look aside; saving Bahrain’s opposition from the king’s guns is not worth the trade off of potential chaos in what would certainly be a flawed democracy.

Iran, meanwhile, can use Bahrain as a pressure point but not as a potential conquest. Such a thing would be a red line guaranteed to trigger a U.S. counterattack that would destroy the Islamic Republic. So Iran may support its choice opposition a bit, but not so much they throw the balance off and create uncontrollable chaos.

The king could reform the government and mollify the opposition as he once did. But alas he does not control his own fate and is a fine demonstration of when leaders don’t really matter. To go too far will upset key allies in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, both of whom hate and fear democracy. With royal factions in Manama who feel the same way, if King Hamad tries to go all enlightened on everyone’s ass, these anti-democrats will have Saudi military support in any coup they launch. No matter what kind of man he is, King Hamad will not be allowed to be the first Gulf ruler to introduce democracy.

With underground democrats multiplying and organizing, the absolutists in the region’s royal courts must hold the line firmer than ever before. Once upon a time, a ruler might have been asked why there was no democracy in his country and reply, “Islam,” and be convincing. But no more. The carrots of heaven and free stuff have worn thin; now they must try the stick of the secret police prisons.

If state power weakens in Saudi Arabia, as it likely will if oil prices continue to flatten, Bahrain is the first raggedy edge that would unravel the entire political fabric of the Persian Gulf. When that fire is lit, it will burn brightly. There are better ways than this; nobody seems much interested in them.

Great work. Bahrain is the future Crimea.

Thanks! I hope history doesn’t repeat itself, but Bahrain’s got too many problems for them to remain isolated forever.

When you said you saw attack helicopters and military armor, you were gravely mistaken. I live in Bahrain and I assure you the helos you saw are for surveillance purposes and the military armor are revamped anti-rioting armor vehicles, no live ammunition on board. Your pieces are entertaining enough, just wish thee was more geopolitical analysis (ones based on interest) in your articles.

Thanks for the input.

I am sure that the shape of the helicopter I saw was a Bell AH-1 Cobra helicopter and that it is classified as an attack chopper. I made sure not to say that it was firing on the neighborhood, but mentioned it as proof that Bahrain’s government takes the protests seriously enough to deploy military equipment in response to them. That’s a different response than riot units, unarmored police cars, etc., that might be deployed to quieter protests, and my intention was to show readers (the majority of whom don’t know much about Bahrain and may have assumed there’s been no news from there since 2011, when last the world media noticed it) that despite the lack of coverage, there remains serious opposition to the government.